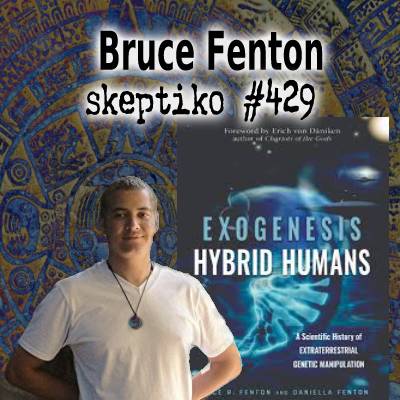

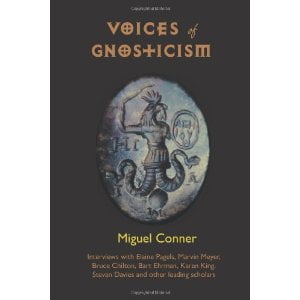

210. Miguel Conner Explores Gnostic Themes and “Red Pill” Alienation

Interview with author and Podcast host examines Gnostic themes in our modern culture.

Join Skeptiko host Alex Tsakiris for an interview with Miguel Conner author of, Voices of Gnosticism. During the interview Conner talks about the limits of Gnostic history:

Join Skeptiko host Alex Tsakiris for an interview with Miguel Conner author of, Voices of Gnosticism. During the interview Conner talks about the limits of Gnostic history:

Alex Tsakiris: You do a masterful job exploring how these threads of Gnosticism are woven into our modern culture, but what about the limits of history? Isn’t Gnosticism limited in the same way Christianity’s limited in that it’s always looking in the rearview mirror for the next archaeological dig to tell us who we are? Isn’t that an inherent limitation of this kind of historical-based knowing?

Miguel Conner: There certainly is, but it goes beyond history. I think the scholar, Ioan Couliano, who wrote, The Tree of Gnosis, said that there’s sort of a binary Gnostic code within man and this binary code will always go off. So, you’re always going to have Orthodoxy on one side believing that the world is going to be fine and that we’re part of this grand history, this providence. But there’s also the other side that’s always there. This side that tells us we are alienated; we are trapped in this world; there’s something wrong with this world. It’s invites us to go on this inner voyage inside and outside of us.

That is why there are many writers and thinkers like Carl Jung and others who before the Nag Hammadi library was discovered were getting some of the Gnostic ideas and concepts. They were getting it very well even with the little information out there. So yes, we are limited by history but again I feel that this Orthodoxy and Gnosticism is within each one of us. That’s why it keeps resurfacing in so many different traditions, whether it’s Buddhist or Muslim and so forth. It’s there.

Miguel’s Aeon Btye Gnostic Radio

Click here for YouTube version

Click here for forum discussion

Play It

Listen Now:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Download MP3 (48 min.)

Read It:

Today we welcome Miguel Conner. As host of Aeon Byte Gnostic Radio, author of the critically-acclaimed Voices of Gnosticism, Miguel is one of the leading voices of this Gnostic movement that we seem to keep hearing so much about. I should also mention that Miguel is also an accomplished fiction writer, having penned several popular post-apocalyptic vampire novels that have really caught the attention of people.

So Miguel, it’s great to welcome you to Skeptiko.

Miguel Conner: I’m glad to be here, Alex. Thank you for having me on.

Alex Tsakiris: You know, I should mention we tried to do this a week ago but we ran into some Skype trouble so we’re going to do it again. In that intervening week I’ve dug into even more of your shows and I just keep wanting to dig more and more. You have such a great insight into this fascinating area of knowledge that is Gnosticism. You weave it into our modern culture and modern contemporary issues in such an imaginative, creative, and entertaining way that I just really wanted to get you on and encourage people to check out Aeon Byte Gnostic Radio.

Miguel Conner: Thank you very much. I don’t know if I can live up to that billing, but I’ll try.

Alex Tsakiris: Oh, I think you can. I’ll tell you what I want to do to tee this thing off. I want to give people a little taste for what you do because it’s really quite unique and it’s a very high-quality production that you put on on your podcast. We used to gather a lot of these elements.

So, Miguel, we can step back and talk about what is Gnosticism. What I thought I’d share and get you to comment on as a way of kicking us off here is the Wikipedia definition of Gnosticism. It says, “Gnosticism is the dualistic belief that the material world should be shunned and the spiritual world should be embraced.” It goes on to say, “Gnostic ideas influence many ancient religions,” and it also says that it advocates philanthropy, sexual abstinence maybe even, and it also, of course, tells us that it’s often associated with early Christianity.

So in the usual Wiki fashion, they’ve probably left it out or maybe totally lost it, but tell us how close that definition is and what are some of the points that it’s hitting that are important to this thing we’re calling Gnosticism.

Miguel Conner: Well, I think it’s a good working definition. It would work but ultimately it’s just the beginning of the journey. I like to see Gnosticism as more of an attitude, which basically centers around “gnosis,” that sort of insight into the other realms, into the Divine realm or hellish realm, as well as an inner voyage into yourself.

It’s more about the truth but it’s also breaking away from the falsehoods of existence around you. The Gnostics would posit that most of reality and unreality is fake and false and there are grains or Divine sparks of ultimate truth that are out there and it is our job to gather these sparks, as the Cabbalists would call it, the Yakum Elohim, and send these sparks through a unification or a higher plane of existence. I’m getting sort of metaphysical but you can translate this Gnostic sensibility to literature, whether it’s Herman Melville or art in the movie, The Matrix.

You can get philosophical as Huxley might, or Carl Jung in a psychological sense. And you can apply this sort of Gnostic sensibility to various facets or fields. To me it’s just very exciting. If you have gnosis, any information that liberates you, that liberates your spirit or expands your consciousness, that’s what people propose—that Gnostics, even though they distrusted reality I don’t think they hated the world. They certainly were full of skepticism for the world and how are you going to find a way to liberate yourself from it?

Some believe yes, aesthetically you have to sort of deny the world and if we are to believe some of the church founders, there are some who believe you have to get sick of the world through libertine rituals, although we don’t know for sure how credible these are. So in a sense, that is Gnosticism. In fact, if you don’t mind, I’ll read you what a friend of mine wrote and I think he hit it on the nail which is:

“Some conceive of Gnosticism as an aesthetic and dualistic mysticism with a message of liberation from the present realm of suffering. Some conceive of Gnosticism as a motive of co-investigation and transformation in which sexual magic is a key component. Some conceive of Gnosticism as a pantheistic world-embracing tradition with roots in nature revealing paganism. Some conceive of Gnosticism as a practical expression of Jungian psychology to which theology is extraneous. Some conceive of Gnosticism as a worldview rooted in the experience of alienation with a modern parallel in existentialism. Some take a combination of these paradigms and others beyond those that are listed.”

I would say that the first and the last is probably a good foundation because after all, Gnosis begins like in The Matrix with taking that red pill, waking up, and realizing ‘Oh my God, there is something greater inside of me than I could ever have thought, but also I’m living in the middle of a false reality. A construct, whether it’s by governments, gods, people, or my own ego and I have to get out of this.’ Another good Gnostic film would be The Truman Show.

Alex Tsakiris: That I think sums up so many of the enticing aspects of Gnosticism and the challenging aspects of it, as well. Let’s throw in a couple other terms and ask for a definition of that. We have this term that pops up a lot which is “The Gnostic Gospels.” People always use air quotes when they talk about The Gnostic Gospels but in real simple terms so people have a grounding on this, what are we talking about when we talk about The Gnostic Gospels?

Miguel Conner: Traditionally, Alex, The Gnostic Gospels are the texts found in the Nag Hammadi library. Not all of them because the Nag Hammadi library is kind of a greatest hits. It’s got Jewish/Christian/Pagan and so forth. But these are the writings found in the Nag Hammadi library and outside of it, like the Pistis Sophia. It probably includes the hermetic writings, some of the cabbala writings.

But these posit and are couched in a sort of Judeo-Christian world and in this world we have a lesser creator god or divine agency that traps the divine spark in this again, sort of virtual reality, this illusionary hell, if you would. Through gnosis, which is usually brought by clarifying mysteries, it could be Jesus Christ, Hermes’ Trip to Medidos, Simon Megas, Mary Magdalene, and so forth. We can transform ourselves or wake up and find our journey back to our ancestral homes. So these are sort of the qualities you’ll find in The Gnostic Gospels.

But having said that, I could say that for example, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is a Gnostic gospel. I can even say The Matrix or The Thirteenth Floor is a Gnostic gospel. Again, I’m trying to extend this into other fields, like literary, philosophical, and so forth.

Alex Tsakiris: There you go again, Miguel. We’re going to have to keep pinning you down. That’s wonderful and I think it’s wonderful in a brain-shifting kind of way that connects us with these very ancient texts and makes them more relevant to what we’re doing. But I do want to try and pin down that history a little bit so we can ground people.

So this is the mid-20th Century; it’s the mid-1950s that the Nag Hammadi library discovered a lot of this stuff?

Miguel Conner: Yes. And The Gnostic Gospels would specifically be 2nd Century Christian heresies that again talk about a demiurge, inner transformation of the self, possible reincarnation; Jesus Christ is one of the leading figures. And from those texts which were written, by some believe, the school of thought called the Sethians or the Valentinians or possibly the Canaans or Ophites, the serpent-worshipers. From there you can start working your way out. In a scholarly way, The Gnostic Gospels, or even the Gnostics would be the 2nd Century groups.

In fact, many scholars today don’t even use the term Gnosticism because after all, it was coined in the 7th Century by an orthodox theologian and it was originally a polemical term that got expanded like paganism. It grew into a term that people didn’t like. So I would start there and then work your way out.

Alex Tsakiris: So in 1945 we discover all these very early…

Miguel Conner: And before that there were some texts like the other Gospel of Mary Magadalene texts floating around.

Alex Tsakiris: And these are heretical in the true definition of the word. Heretical to Christianity…

Miguel Conner: That’s another problem, yes. The term “heretical” originally wasn’t as negative as we know today. The term “heretical” first really meant a school of thought, like Flavius Josephus and “I’m a heretic of the doctors.” He was a school of thought of the doctors. Then the term which comes from the Greek is for “to make a choice” became in the 2nd and 3rd Centuries simply a word for those Christians who had made a choice beyond the norm. They were on the fringe. And then it just gets worse and worse. But they are heretical, yes.

Alex Tsakiris: Okay, so when the 1940s rolls around and we discover these texts that are very, very much in conflict with—really you can’t say it another way—the way the Judeo-Christian tradition has been Westernized and the way that it’s practiced. So this starts developing, would you say, this spark among certain people to say, “Wow, maybe even in our Western tradition we can find something we would normally have thought of as more Eastern in its philosophical outlook.” Let me stop right there because I may have said something else that isn’t correct. What are the ties between this early Christian Gnosticism and some of the Eastern traditions?

Miguel Conner: Well, the ties probably have always been there. We do know that there’s always been from the Silk Road a trade of Eastern and Western traditions. Even before the Gnostics, before Christianity there were Buddhist priests or monks in Alexandria, before the 1st Century going there. There were Romans going there for spices. So these ideas were back-and-forth. You look at something like a big influence on the Gnostics would be the Cult of Orpheus that believed in reincarnation and divine spark. The Cult of Bisagras.

So this thing was in the air and in fact, some scholars have said, “Hey, it’s very possible that the Syrian mystics and the Gnostics actually influenced the East in some of the later traditions of Hinduism and some of the ideas of Buddhism.” So the relation in a more primordial manner, when the Gnostics were around other Christians around them shared a lot of these ideas. It wasn’t anything heretical. This is sort of later when you have to make the religion mainstream and marketable.

But again, this idea that we have an inner god within us, each one of us, that we can access through the right rituals or contemplation, the idea of reincarnation, of insight into the world and how the world is simply an illusion that we have to break through, these were shared by the Gnostics and the Easterners and even many of the Christians and Jews. It was not heretical or even controversial at the time. It was in the air across the world.

Alex Tsakiris: And that gets to one of the problems with Gnosticism as we try and define it because as you just described, to a certain extent it’s defined by the religious structures that it undermines. I mean, Gnosticism is to a certain extent defined by the Judeo-Christian tradition when in fact, the history of Gnosticism suggests that the Judeo-Christian tradition isn’t what we have come to believe that it is, right? Isn’t there kind of a paradox there?

Miguel Conner: Yeah, yeah. Scholars have said, including Elaine Pagels and so forth that there was no original Christianity in the 1st, 2nd or even the 3rd Century. It was all this giant speculation of ideas and different little schools of thought that congregated here and there and exchanged information with the pagans and the Jews in Alexandria and so forth. There was nothing ever said.

For example, one of the great Orthodox Fathers, Clement of Alexandria said that the only true Christian is a Gnostic, one who knows, one who has gnosis. Other church Fathers said there is a demiurge. This world is divided by these demons, as they called them. So yes, you can easily say that there was never a formalized, organized Christianity that went out with the Apostles and so forth. It was a very speculative and imaginative time, those early days of Christians. The Gnostics were part of that group.

Alex Tsakiris: And then following that Gnostic path forward, how do we differentiate that from modern ideas of enlightenment or awakening?

Miguel Conner: Well, the main difference is that our world is created by lesser agencies or even evil agencies, which you really don’t find anywhere. In fact, some Gnostics said that we as humans were simply sort of fleshy cases in which the divine spark was hidden from the true god or the higher forces like Sophia. So that right there is pretty much unique.

All traditions would like to say I can know God or I can experience God and have a mystic thing and of course that’s great, but to the Gnostics it was more of an intellectual exercise but also a spiritual exercise. It was very in-depth, going into the various levels of who you were as a human to find this divine spark. Even Carl Jung said the Gnostics were the original psychologists because they went deeper than pretty much any of the Greeks or philosophers out there.

Then it was an outer ride into the different planes of reality or consciousness which you don’t find in any size or depth as you do with the Gnostics. So that right there, you’re getting into some very unique characteristics. But of course, as you said, no religion exists in a vacuum. Every religion exists in a state of hybridity where they borrow, take, and interact with other religions until they all overlapped and they continue to overlap even to this day.

Alex Tsakiris: Interesting. Another thing I want to get out there, because you just touched on it again, is this reference to the dark side. To the occult, to evil in its different forms as we think about it. I think there’s an association that a lot of folks have between Gnosticism and the occult and the dark elements. I think you’ve done a nice job already of showing us how those distinctions might not be exactly what we’ve been conditioned to think they are. Can you maybe touch on that some more?

Miguel Conner: Yeah. Of course this is why Gnosticism or the Gnostics have always been so endearing to so many artists throughout history. We can go to William Blake and Philip K. Dick and a whole slew of others. You’re almost going to hit that Gnostic sensibility because it does begin by taking the red pill and before you take the red pill you do feel an alienation. Like Morpheus said, there’s something wrong in the world but you don’t know what it is and it’s like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad. You feel alienated, like something is wrong. I think more and more people in this society, with the media and everything that’s going on, probably feel that way, and they did in the Roman times.

It starts with that alienation and that search for the truth, for reality. As you seek that reality you take the red pill. You realize that everything that you were taught or you believed is probably wrong and everything that you are is really a construct. A construct of faith, of society, of dark, shadowy forces. The man behind the curtain. But at the same time, there’s this beauty. Again, you see how the universe is really there’s this light hidden beyond the universe and beyond that there’s what they call a Sophia. The Gnostics called it “the alien god,” which is this force beyond all forces that calls you to it. But of course, you have to do the work and meet these beings half-way.

So in that way, that’s why not just artists but occultists have felt so drawn to Gnosticism. It’s that sense of alienation, that sort of skepticism to the world, that artistic impulse to go out and find something that’s better than what has been presented to us. Some people have called the Gnostics the “original geeks” or “original conspiracy theorists” because they were asking these questions long before anybody. They thought there was a conspiracy in every rock and every human and they wanted to analyze it, break it down, and at the same time have enough compassion to show others to find their own inner light.

Alex Tsakiris: But what about that connection with the dark side? How do we dance in the shadows? Is Gnosticism one foot on the banana peel away from Satanism like a lot of people will tell you it is?

Miguel Conner: Satanism is like paganism. It’s an umbrella term you throw here and there.

Alex Tsakiris: It’s a very recent term, too. Really, if we’re going to be historical about it…

Miguel Conner: Right. If you read history there have been strange people who made blood sacrifices for Satan. They’re still within the Christian mythology, they’re still in the narrative. So they’re just Christians gone wrong. But with Gnosticism, of course the idea of gnosis is first the old Oracle of Delphi saying, “Know thyself.” To know thyself is not to just sit there and go, “Oh, I’m a beautiful snowflake. I’m a piece of God.” No, it’s knowing that you are also made of some very dark forces.

If Jesus and the Kingdom of God is within you, well logically the Kingdom of Hell is within you. Most of what you are is probably a construct of faith, of society, of cosmic forces, stars, and you have to know the dark side of the world. But in knowing it you will hopefully find the answer on how to break out from it. So again it really starts with knowing thyself.

Alex Tsakiris: Miguel, you really do a masterful job on Aeon Byte Gnostic Radio of weaving these threads of Gnosticism into our modern culture. You’ve just done a nice job of doing it here. I do feel also though that you’re open, as you describe on the show, to the limits of history.

And we understand that history is written by those who conquer. We have to wonder if the Nag Hammadi library would even be in existence if Genghis Khan took one turn or another and burned the library like he destroyed the greatest library in the world in Baghdad and burned it to the ground. What uncharred documents are left is what we’re really basing a lot of this on. Isn’t Gnosticism limited in the same way Christianity’s limited by this always looking in the rearview mirror for the next archaeological dig to tell us who we are? Isn’t that an inherent limitation of this kind of historical-based knowing?

Miguel Conner: It certainly is but it really goes beyond history. I think the scholar, Ioan Couliano, who wrote The Tree of Gnosis, said that there’s sort of a binary code within man and this binary code will always go off. You have Orthodox on one side making things mainstream, believing that the world is going to be fine and that we’re part of this grand history of providence.

But there’s also the other switch, the other side that’s always there. We are alienated; we are trapped in this world; there’s something wrong with this world. Let’s go on this inner voyage inside and outside of us. As he posited, you get this erase the Bible in every religion. In 100 years the binary code will go off and somebody will go, “I am Orthodox. This is the way it is,” and immediately somebody down the line will say, “No, there’s an opposite sensibility. This is the way it is.”

That is why there are many writers and thinkers like Carl Jung and others, before the Nag Hammadi library were getting some of the Gnostic ideas, the names, and the concepts. They were getting it very well even with the little information out there. So yes, we are limited by history but again I feel that this Orthodoxy and Gnosticism is within each one of us. That’s why it keep resurfacing in so many different traditions, whether it’s Buddhist or Muslim and so forth. It’s there.

Alex Tsakiris: Excellent. More evidence that it is truly an innate spark in us and maybe even a divine spark, as you said. It almost serves as evidence that it is there and it is timeless. Fascinating.

Let’s talk for a minute about the other dark side, the Atheists, because you on your show are very charitable to the Atheists and give great praise where it’s often due to folks like Bart Ehrman, Biblical scholar, Robert Price, and others who have a view that I think is counter to this basic idea of Gnosis. How do you see the Atheistic, materialistic worldview fitting into this larger picture of this divine spark?

Miguel Conner: Obviously I wouldn’t be certainly against it. I mean, I do admire the part that the Atheists would say to the Gnostics, “Hey, use your reason.” The Gnostics, even in their texts, talk about how science and art and literature will free you. That’s part of gnosis that expands your consciousness. I do like that the Gnostics and the Atheists would share the idea of being free from mainstream religions and the grip of tyranny and government and so forth, but at the same time, that’s where we part the way because the Gnostics are about the divine spark.

You can change divine spark to more modern terms such as consciousness, a great mystery that not even Sam Harris, one of the popes of Atheism, says that’s the one thing science and materialism has not figured out. They may say that around the corner they’re about to discover consciousness. They’re going to discover the flying car or the God Particle. But the truth is they won’t. It’s a great mystery.

So in that sense, the idea of consciousness and the divine spark and obviously Atheism can be a little bit more—I’m going to say—materialistic. Atheism sort of has a positive view of all that is material and all that we can see. The Gnostic sensibility would certainly reject that and say, “No, it’s all a lie. Ultimately it’s a lie and very little is going to be true.” So that’s where they part ways.

Alex Tsakiris: Well said. But there’s a great divide between Atheism and if we’re going to lump together spirituality in its broadest terms, in a big tent way, and throw Gnosticism in there and all our religions in there and New Age traditions, all that stuff, that’s one big tent. The folks on the outside of that tent are saying, “No, no, no. Your experience is nothing. You are merely your brain. You are this materialism. You are this biological robot.” Isn’t that more of a divide than we’re letting on when we let these people into the tent?

Miguel Conner: Yeah. Obviously you have to go sometimes with the “enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Try to find some common ground because I would hope that most reasonable Atheists just want to get along and go about their business, which is what the ancient Gnostics tried to do. They’ve been wiped out throughout history, so the Gnostic Ethos would say, “Well if we could find groups to get along, let’s do it. We do agree that 99% of what we are is all organic or an illusion. Well, we agree on that—maybe we can agree on the mystery of consciousness.”

Alex Tsakiris: Interesting. And maybe that’s why New Agers get your ire so much. Do you want to speak to what it is about the crystal crowd and the secret crowd that so riles you up so often on your show?

Miguel Conner: Oh boy. I’ve done many rants and ravings, probably because I used to be a New Ager before I started reading The Gnostic Gospels. The problem I see is again they fall into the same materialistic trap as do others except sometimes worse. It’s calendars and diets and books for everything that’s New Agey. But it’s the idea of how they confront suffering, and this is where they fall short. Even shorter than Atheists or Theists because somehow suffering is relegated over away from the moral realms and simply put into a sort of pseudo-psychology state. Suffering is just an illusion; you don’t have to worry about it. Everything is about self-development and everything is going to be okay.

They take it even more to the extreme than the Abrahamic religions that at least want to address suffering in the world. That’s my big contention with so-called New Age. I remember when I truly left the New Age movement, I was reading a book by Gary Zukav and I really liked The Seat of the Soul. But I kept re-reading it and there was a passage where he said, “Well, if you see somebody on the street who’s poor and hungry and has no clothes, just remember, he has a karmic duty so don’t worry about him. He’s got to fulfill his karmic duty.”

And that goes against the Gnostics or the Christians or even the Atheists. You can’t just relegate people to the powers of fate or karma or the change of being of the Neo-Platonists. No. It’s about being a human and finding your divinity is to help other human beings. It’s just basic.

Alex Tsakiris: So it’s the narcissism and the hypocrisy, I guess, that you rail against. So if you’re going to be a hedonist, at least be a full-blown Atheistic hedonist. Don’t go half-way and call yourself a New Ager and really be a hedonist behind all that.

Speaking of New Agers, I want to bring up Shirley MacLaine because I heard an interview with her the other day and of course, she’s one of the original New Agers and had a lot to do with the New Age movement with her astral projection and all the rest of that stuff. But the quote that she gave—because she’s obviously a famous movie star—was that they were pushing her and she said, “Hey, you know what? We’re all entertainers at the end of the day. That’s what we do. That’s our life mission for everyone is to entertain everyone else.”

I thought that was particularly relevant to your show. You’ve put a high production quality in your show. You obviously care about engaging your audience in a way that is entertaining. What part does that play for you in your own personal understanding of Gnosticism and gnosis?

Miguel Conner: I think Shirley MacLaine is actually being very insightful because the truth is—and most people forget this—the Gnostics and even the first Christians were artists as much as they were theologians or mystics. After all, the idea that you have to express something that cannot be expressed, knowing the unknown, you’ve got to put it in a way that people learn. Allegory, mythology, a parable. Jesus was about parables because he knew nobody would get it.

Then you have these texts that were never meant to be read because nobody read. But they were actually sang. They were used as poetry. Willis Bartenstein, the great Shakespearean translator who worked with Horkelia Borstkas who was also another great Gnostic, he said that one of the characteristics of the Gnostics has been always being the greatest artists of their time. You can go to the Middle Ages with the Cathards. Their hymns were just gorgeous. You can look at the Manicheans of the Middle Ages and before. They loved drawing and writing this great poetry.

So these world-hating, existentialist, alienated Gnostics were beautiful and as she said, entertainers first. There’s nothing wrong with it because you’re expressing something that is so amazing the best you can do is sing. St. Francis of Assisi, most people don’t know he used to put on plays to describe every gospel in the little town. He did these amazing theatre productions to do the Gospel of John or whatever. You’ve got the divine spark lights within you; you know things are bad so the best thing you can do is do a little song and dance.

Alex Tsakiris: It’s interesting, this artistic thread that you’re going down as a way of expressing this divine spark. We’ll keep using that term.

What I want to do is juxtapose that with science. I’m just wondering what are some of your thoughts in terms of what role modern science can play in helping us probe these questions in a new or different way. We are very much a scientific culture along with being an Atheistic culture. How might science play a role in moving this gnosis forward?

Miguel Conner: Well, obviously science plays a role. There is the Valentinian Theodosius. He said science actually makes our faith stronger because what’s out there is out there but the gnosis (“knowledge” from the Greek) also is about calibrating your brain, making your mind into a stronger antenna so that it can commune with the other antennas of the higher mind or the muse, as the Hermetics called it. So science guides us but art inspires us. To me that is gnosis. It’s a beginning of gnosis. There are two pillars of gnosis, if you will.

Alex Tsakiris: That’s a great quote. There’s another quote, one from the Dali Lama that takes it in a different direction and says—I’m paraphrasing, of course—but basically the idea was that all of the ideas that have been around for centuries within the Tibetan/Buddhist tradition are open to verification by science. And if science wants to prove that anything is false, then of course Buddhism would have to change because Buddhism is about the pursuit of the truth.

So do we need to put this kind of science first sensibility out there, or is that consistent with Gnosticism?

Miguel Conner: Of course it would be consistent because the Dali Lama’s right. After all, in Buddhism what are you looking for? You’re looking for a higher expanded state of consciousness. An emptiness within you. Of all the things that you are so that what is real can flow through. That goes right into what the Gnostics would say, you know? To get rid of everything that’s false in you and let that divine spark a.k.a. consciousness expand until you reach that silence, that ethereal sublime state. So there’s nothing wrong with that. And science is a great help.

Alex Tsakiris: Miguel, you mentioned a minute ago that Gnosticism isn’t dependent on a certain history and that the divine spark will emerge and continue to emerge no matter what path we fall down in history. Let me play Devil’s Advocate. Ray Kursweil is a guy who’s come up on your show and he’s come up on my show, as well. He’s the famous futurist who talks about singularity, that is that point sometime in a future that we can really see advancing a lot faster than we could before when technology will equal human intellect as we know it.

And when that point is reached and then exceeded that we will be in a whole new realm, one that we have never anticipated at any point in history. We’ve never experienced it at any point previous and that it will redefine who we are. What does Gnosticism have to say about this view of human consciousness merging with the machine? With the divine spark, if you will, merging with the machine? Any thoughts on that?

Miguel Conner: The problem I have with the singularity view and the proponents of them is that I think that it plays too much on the apocalyptic mentality that’s out there. It sort of exploits a very true Gnostic idea that we are dissatisfied with ourselves. All of us are sitting here in the desert of the average in our cubicles and our homes and our families. Instead of looking inward for what is real right now, we get caught on the possibilities, these hopes for a better world. The Mayan Apocalypse craze is the last great example of how Christians are always looking for the end of the world.

In fact, there’s a book by John Greer, Apocalypse Not, where he studies it and he says people want something in the future, even if it’s carnage and brimstone from heaven because it gets them away from the mundane reality they are in now. Again, singularity plays on it that we will, in the future, become gods or united with the machines or have these mechanical consciousnesses instead of focusing on where we are now and what is wrong now with ourselves. Again, taking that journey inward.

Alex Tsakiris: Great. Speaking of future, Miguel, tell us a little bit about what’s going on with you in the future. What’s coming up on Aeon Byte Gnostic Radio and other projects you might have in the works.

Miguel Conner: Well, at this moment in time I’m sort of status quo. I keep trying to get these great guests, these mid-wifers of truth that come on. For example, I have a show on Freemasonry. I have another guest talking about the different Gnostic churches because they are out there. In the 19th Century there was sort of a Gnostic revival when these churches started coming about, including Crowley did a Gnostic mass and so forth. So there are still a lot of places and guests out there who are part of the Gnostic taproot. So I’m working on that.

I’ve got another novel that I should be finishing for a publisher, and a new nonfiction article that I’m writing for a different publication. I am in my own little corner of the universe like you are and we’re over here just trying to open some more doors so people can make their own choices and go on their own adventure to find the divine spark, the true self, the higher self. We’ll see what happens. I don’t expect to change the world. I don’t think the Gnostics did. But we can help one life spark at a time, as the Calvinists would say.

Alex Tsakiris: Well said. Let’s hope that a few more folks can find their way over to your little corner of the universe by virtue of this show. I certainly hope that people do check out Aeon Byte Gnostic Radio. You’re in for a great ride if you do. Not only great content but great guests, as well. I’ve become a regular listener and can’t wait for the next episode.

It’s been great having you on, Miguel. Thanks again for joining me today on Skeptiko.

Miguel Conner: Thank you, Alex, it was great being here.